Labour wants to ‘bring maths to life.’ These primary schools are already doing it.

‘Knowing how to add and subtract doesn’t make us great mathematicians, just like knowing how to spell and use proper grammar doesn’t make us great writers.’

Bringing mathematics into the real world for the youngest learners is a hot topic these days in England.

Shadow Education Secretary, Bridget Phillipson, told the Labour Party’s 2023 conference her party is determined to “bring maths to life for the next generation” and to ensure the numeracy all young people need will be part of their learning from the beginning.

“Because be it budgeting or cooking, exchange rates or payslips, maths matters for success,” she said in her speech.

But what does it mean to bring maths to life? What does it mean to say maths should be more ‘real world?’

Covid-19 provides a good example. The recent pandemic highlighted that “many people in England were baffled by terms such as ‘moving averages’ and ‘exponential growth,’” says Dr Pete Wright at the University of Dundee.

Socio-mathematical agency

Wright and his colleagues set about studying how to develop ‘socio-mathematical agency’ in primary pupils. They define SMA as the ability to use mathematics effectively to argue collectively for social change.

“In an increasingly information- and data-rich world, individuals are expected to understand complex mathematical ideas to make sense of their own situations and take decisions that will promote their own well-being and the ‘public good,’” Wright says in a research report. “It is questionable how well schooling currently prepares many learners to do this.”

Covid-19 is as real-world as it gets, but there are plenty of less threatening opportunities to bring the beauty and utility of maths home to children.

Oxford University Professor Dr Marcus du Sautoy, OBE, says as a mathematician he’s fascinated by how many people in the creative arts — musicians, visual artists — and the humanities have told him they wish they’d been given better mathematical tools.

Mathematical structures

“They understand that a lot of the structures they’re trying to use in their own work actually have a very mathematical character,” he said on the sidelines of the 2019 Maths — No Problem! annual conference. “I only wish we could have told them about these structures while they were at school.”

I discussed real-world maths on a recent episode of our School of School podcast with my colleagues Adam Gifford and Robin Potter.

My point was that maths isn’t about remembering random facts and arbitrary procedures, but rather it’s about applying those facts and procedures in a meaningful way. It’s about having the language to describe the world, to be able to say things like, ‘Joe is twice as tall as his son.’

Knowing how to add and subtract doesn’t make us great mathematicians, just like knowing how to spell and use proper grammar doesn’t make us great writers.

Adam, a subject specialist and series editor for our Maths — No Problem! New Edition, put it this way: “Children need to know there’s more to maths than passing an exam. Is that what we want, a society that just has to pass an exam, not apply it?”

Transform Your Maths Assessment

Insights — our online assessment tool — gives you instant, powerful data to identify gaps and improve results.

This ‘pass-an-exam’ mentality gives a false impression of what a mathematician is, he says. “These people are problem solvers. They’re not sitting there just to purely add something up.”

Bringing maths into the real world is something we take very seriously, because there’s a lot at stake, not only for the pupils, but also for the wider world.

Universal basic skills

Respected Stanford University economist Eric Hanushek’s theory of ‘returns to skills’ is rooted in the idea that skills and knowledge, particularly cognitive skills acquired through education, have a significant impact on an individual’s economic productivity and on the overall economic performance of a country.

In a 2022 study, Hanushek and his colleagues Sarah Gust and Ludger Woessmann looked at how close the world is to reaching the foundational goal of universal basic skills for all young people and what reaching that goal would mean for global economic development.

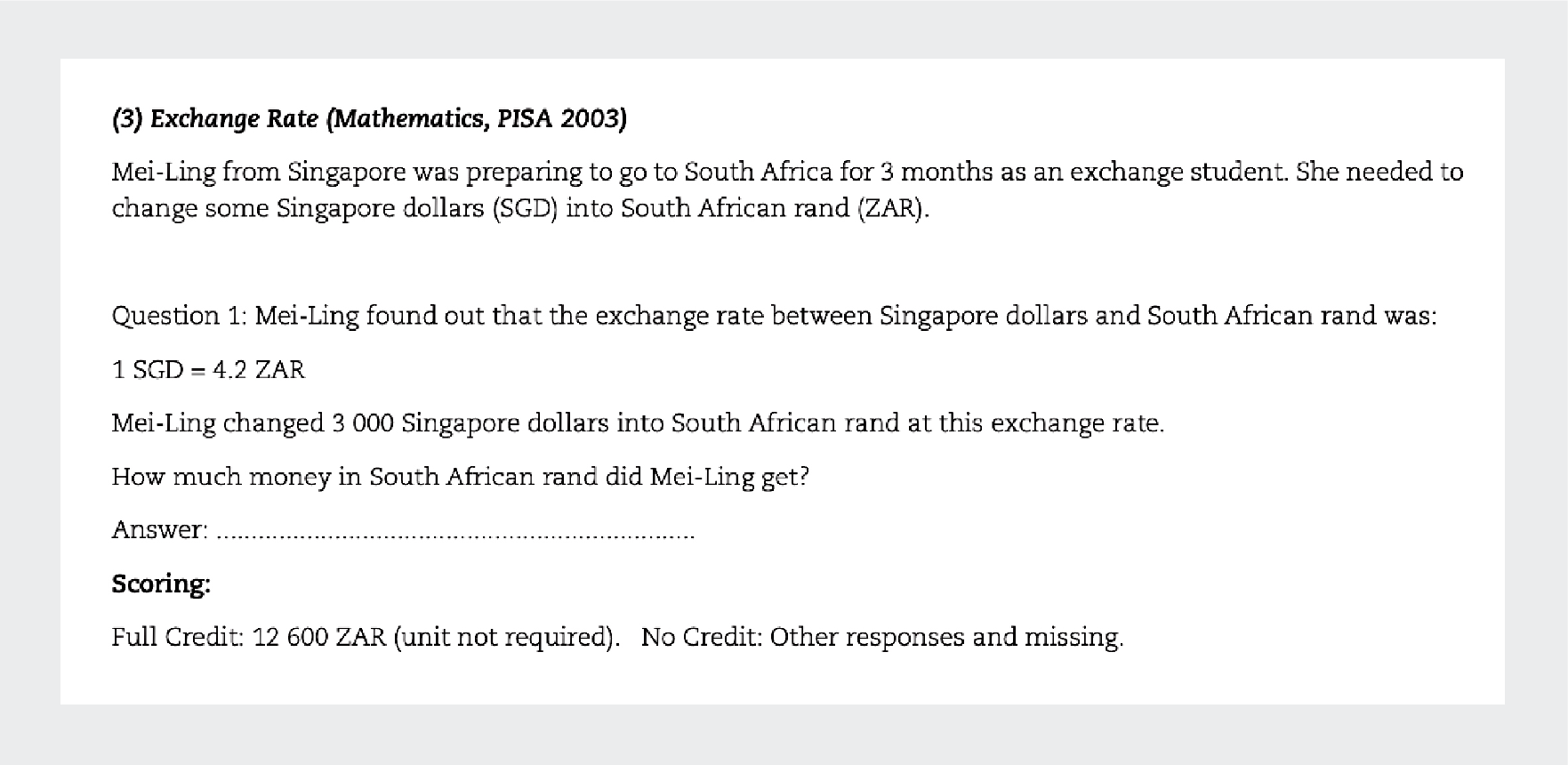

The researchers define basic skills as those necessary to “participate effectively in modern economies,” and as their benchmark they use the ability to master skills at Level 1 — the most basic level — of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) standardised achievement tests.

Basic skill levels, they say, are the modern equivalent of basic literacy, which includes the capacity “to reason mathematically and use mathematical concepts, procedures and tools to explain and predict situations.”

Here’s an example of a Level 1 PISA test question:

In the UK, almost one in five children lacks these basic skills.

What would happen to the UK economy if all children attained the equivalent of PISA Level 1 basic skills? According to Hanushek, the economy would grow by an additional 3% every year.

That’s an incredible amount of money! To put that into perspective, it would pay for about two-thirds of all government education spending.

The impact on the global economy would be staggering. By reaching the goal of PISA Level 1 basic skills for all its young people, the world would gain USD $732 trillion in added GDP over the remaining century, according to the report’s projections.

However, there’s a long way to go. Two-thirds of young people worldwide currently lack these basic skills.

‘Great for geeks’

How do we move towards the goal of universal basic skills when there are still so many pupils in our schools who believe they can’t do maths?

The answer is to make maths more engaging, more accessible and more interesting.

“Very often the way we teach mathematics is great for the geeks and nerds, but sometimes you need other stories to bring in people who don’t find mathematics immediately accessible,” Dr du Sautoy says.

He argues maths is often taught like a musical instrument, where students are only allowed to practise scales and arpeggios and never allowed to hear any real music.

‘Honeycombs are hexagons’

Primary school teachers have an opportunity to tell stories about maths that connect to things like music and nature — honeycombs are hexagons, why is that? Cicadas use prime numbers, how are they doing that?

“We need to, in school, tell people some of the big stories.”

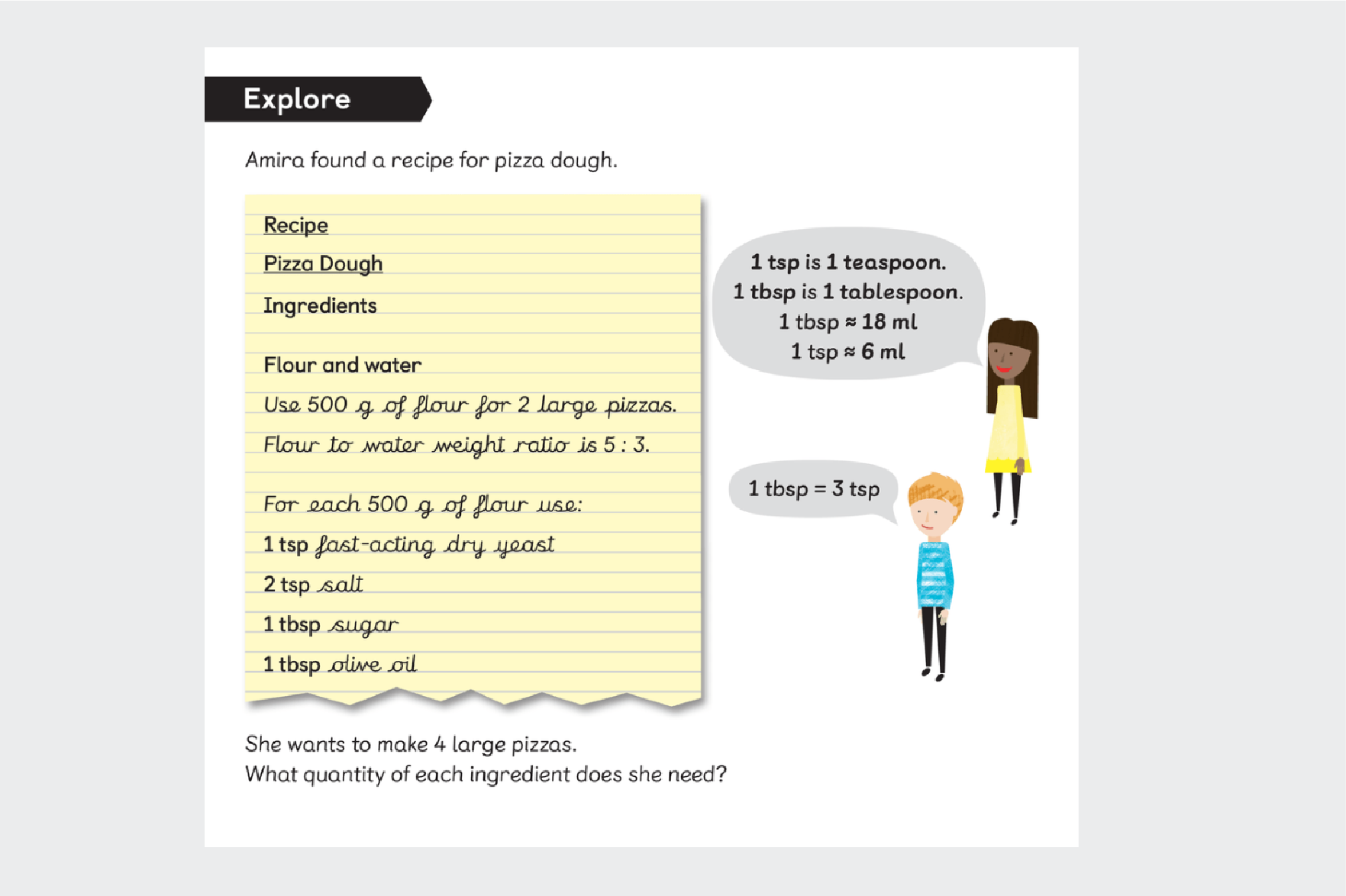

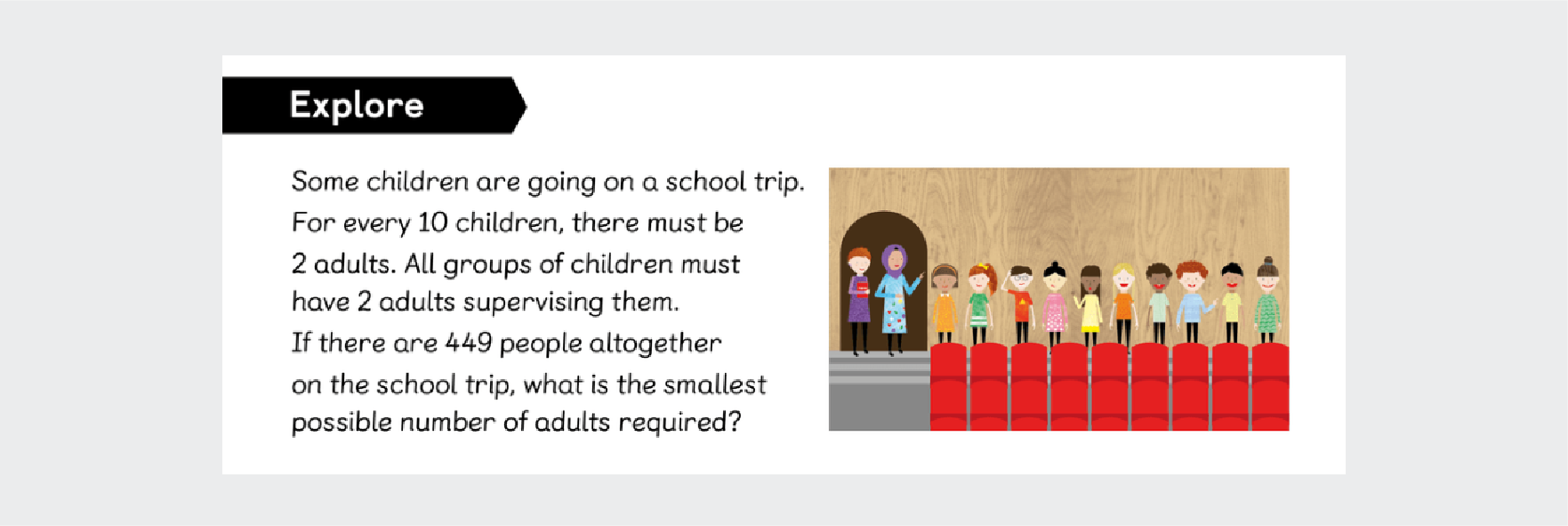

Mastery programmes such as Maths — No Problem! are so effective at building fluency because they help pupils connect maths to their everyday lives. These examples from our textbooks show real-world situations can be used to explore maths concepts in an engaging, meaningful way.

Fluency is often associated with the ability to rapidly recall facts. However — to carry my linguistics analogy a little further — that’s like saying someone who can rattle off a bunch of German words is a fluent speaker. A large vocabulary certainly helps, but fluency requires the person to know precisely how and when to use those words.

The Wright study I mentioned earlier provides some insight into how making maths meaningful — bringing it into the real world — can help children become more fluent.

Fun activities

The three authors — Wright, Dr Caroline Hilton and Mr Joel Kelly — worked with six teacher-researchers to develop effective strategies for enhancing the socio-mathematical agency of pupils in Years 1, 2, 5 and 6 at two London primary schools.

They applied mathematics to issues such as: finding the fairest voting system to choose various fun activities; considering different options for addressing environmental issues such as deforestation and pollution; and analysing how classmates commuted to school.

The teacher-researchers found:

- Providing students with meaningful activities over which they feel greater ownership leads to increasing levels of engagement

- The activities resulted in students becoming more willing and able to apply maths to solve real-world problems

- Engaging with meaningful problems enhanced students’ learning of maths and fostered more positive attitudes towards the subject

- The students became more competent in using maths to strengthen their arguments relating to social justice issues

- Students became more willing to engage in collaborative tasks involving maths and problem solving

In other words, to bring maths to life, make it mean something more than passing an exam.

A good way to see first-hand what this looks like is to attend an Open Day at one of our Accredited Schools.

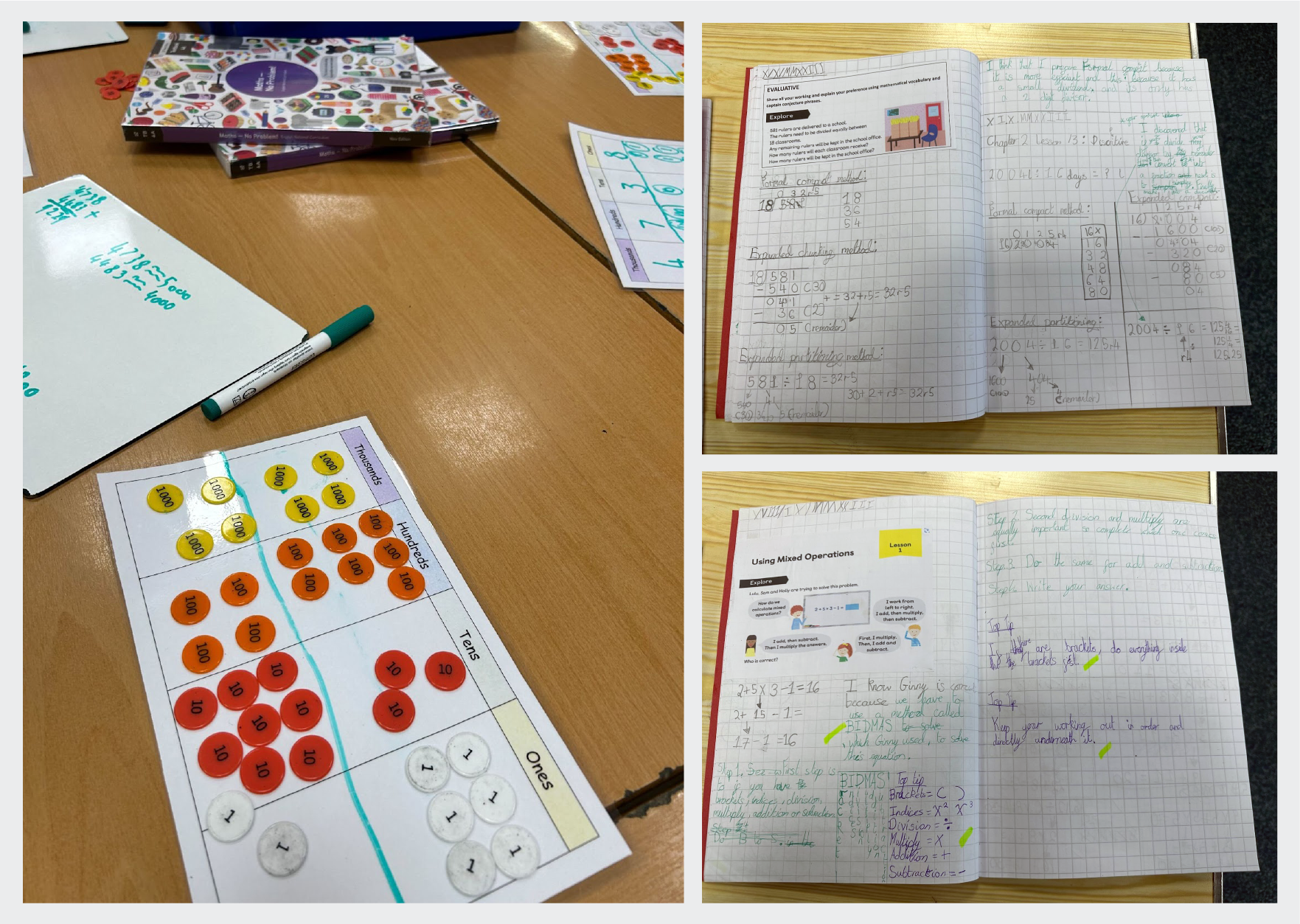

Two of our schools, Orrell Lamberhead and Rosetta Primary, opened their classrooms in October to show visiting teachers and staff what Maths — No Problem! looks like in action.

These schools have focused for years on teaching real-world maths.

Open days showcase a day in the life of a Maths — No Problem! Accredited School. Five or six nearby schools will usually send staff members, usually newcomers to the programme or those who are curious about the approach.

Visitors are welcomed into vibrant and dynamic classrooms where teachers engage with students in a way that challenges traditional maths education norms. The focus is on fostering mathematical thinking by engaging in lively discussion and problem solving.

The maths lead usually kicks the day off with an informal discussion about the school’s Maths — No Problem! experience. They share tips and anecdotes and answer questions.

That’s usually followed by a tour of the school, either the whole school or particular year groups, often the year groups the visiting teachers are working with themselves.

Visitors observe various lessons tailored to different age groups and watch as teachers demonstrate how they apply maths mastery techniques across the curriculum.

Open Days usually finish with a Q&A with staff and a chance for visitors to look through materials such as journals and workbooks. They can also look at the Teacher Guides and other online resources.

“The results show that our children have mastered maths, and I think Maths — No Problem! takes the children further than the expected and greater depth standards,” Keri Edge, Executive Headteacher at Scott Wilkie Primary School in London, another Accredited School that holds Open Days, said in an interview before the pandemic. “All our children now have that mindset of ‘I can do maths.’”

It’s a mindset we need to foster if we’re to move beyond the ‘pass-an-exam’ mentality.

I encourage Ms Phillipson, and anyone else who is serious about bringing maths to life, to visit one of our Accredited Schools and watch Maths — No Problem! in action.

I hope you’ll join me in my quest to raise the quality of mathematics education worldwide. Every child has the right to learn basic skills and become confident in maths, not to pass an exam, but to participate in the opportunities of the real world and contribute to solving some of its problems.