4 ways parents can engage with their children’s primary maths education

Editor’s Note:

This is an updated version of a blog post published on November 9, 2020

Every generation observes learning differently. So how can we make sure that parents are best supported to make the learning experience for their children as positive as possible?

These differences, whether based in fact or not, can have an impact on the next generation’s learning. Giving parents and caregivers support, not only with the mechanics of maths but also with their attitude towards it can be hugely beneficial for all involved.Here are four tips to help you navigate the relationship between parents, their children and learning maths.

1. Debunk parents’ maths myths

To a parent, maths looks different today compared with the maths undertaken by previous generations. Aspects of a maths mastery approach such as the use of Concrete, Pictorial, and Abstract representations (CPA approach) and bar modelling have a far more significant presence in classrooms now than generations before.

Sometimes this can be a double-edged sword. When taught well, these approaches can greatly support children’s learning, however for parents, family and friends at home, it may appear to be maths well beyond their reach.

You need to send a clear message home to support parents’ understanding and allow them to see the many benefits a mastery approach can bring.

This starts by debunking some maths myths.

Debunking the idea maths ability is down to genetics

Our ability to understand the brain and genetics is far better now than it used to be. Research strongly suggests we are not born mathematicians or born with a set capability for maths. Just because a parent may find maths difficult it is in no way indicative of what their child’s experience will be.

It’s important to take a starting place of believing that every child is capable of learning maths. As long as the conditions for learning are right, any child has the ability to learn. They may learn at a different rate to others but their capacity to learn is there.

This is the main tenet of the maths mastery approach.

Debunking the idea that maths today is completely different

We need to remember that maths has been studied and documented for thousands of years. A lot of the maths ideas we used today have been used for that length of time too.

Where things may have changed are the representations we use when problem solving. Heuristics and methods that help to solve a problem quickly, have far more mainstream use in mathematics today.

Take this problem for example.

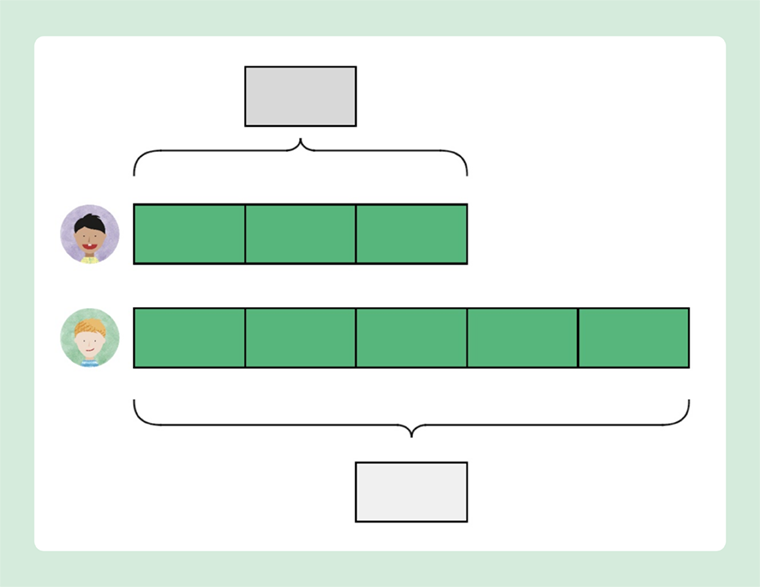

Ravi and Sam have saved £192 between them. The ratio of Ravi’s savings to Sam’s savings is 3:5. How much money would Sam need to give to Ravi so they both have the same amount?

Of course, this could be worked out entirely in the abstract. However, we can also use bar modelling to show the same problem before we get to abstraction.

At the very least, this representation makes it easier to see that Sam needs to give Ravi one part or one unit. If we know this we can start to break down each step in the problem.

Making parents aware of why we represent maths problems with these methods is a great way of involving them in their child’s learning — helping them engage fully with their children’s primary maths education.

Boost Your Practice with FREE CPD

Receive a CPD boost every time you refer a school! Both you and the referred school will earn a full day of CPD and 2 free places on our 3-day Essentials of Teaching Maths Mastery course (valued at £1700).

Get started on helping struggling schools reach maths success now!

2. Let parents know their children are also teachers

Practicing a problem with your learners in the classroom, with the intention of them taking it home to teach their family, is a wonderful way to introduce what could be brand new representations.

Encouraging children to ask their family how they would complete the same problem supports a shared understanding. We have to accept that some parents may find questions, like the question above, intimidating. But talking about this with the children, stressing that their parents may have never seen a bar model before, can be beneficial for both parents and learners.

3. Invite parents into the maths classroom

Having maths open days where the children teach the parents can demystify the maths that takes place in their child’s classroom.

Preparation is the key to this. It’s a good idea to go through the maths lesson with the children before the open day to ensure that they have not only understood the key ideas but have also had an opportunity to practice and develop the language associated with those ideas.

You might also want to ensure that the children understand how the CPA approach can be used in that particular lesson. Being open and transparent and allowing the adults to become learners in the classroom further supports their understanding of their child’s mathematics.

4. Encourage parents to be teachers

It is possible that our parent community will represent a wide range of educational experiences that may include schooling in other countries. Understanding this and seeing this as an opportunity to learn from them benefits both adults and children.

Ask your parents to show you an example of a maths question or problem that they may have completed at school.

- Can they show you how they would complete it?

- Would you complete it differently?

- What can you see is the same and what can you see is different?

- If your parents are from a different country, what do they notice is the difference between the way you complete your problems and how they would complete their problems?

Exploring these mathematical topics can benefit parents and children. It reinforces the idea that at the heart of a problem or question, the main maths idea is often the same.

Not only that, it gives all of us a chance to value the representations from other countries and by understanding this, deepen our understanding of the mathematical ideas attached to it.

Parental engagement is a vital part of a child’s learning. We need to accept that parents may have a less than positive view of mathematics and may find the subject difficult. Being open about the mastery approach and giving parents an opportunity to hear their children talk with confidence and eloquence about the subject of maths can go a long way in forming a learning partnership that will be positive for all involved.